As I said in my original post, there are two distinct aspects to the LIBOR manipulation story. My previous two posts have addressed the possibility that LIBOR was being routinely manipulated by traders to suit their positions. But the alleged manipulation during the crisis of 2008 was of an entirely different nature, done (presumably) not to profit from existing trading positions but rather to obscure from the public the true depth of the on-going crisis by submitting too-low estimates of the cost of borrowing. At first glance, this “manipulation” seems more troubling than that discussed previously, primarily because the intent seems to be precisely to deceive. But I do think any judgment must ultimately take into account the context of the crisis itself and what was going on at the time. It is not my intent here to pass my own judgment on the matter, but rather to present what I think are relevant issues for anyone wishing to consider the matter before they condemn Barclays (or anyone else) for their actions.

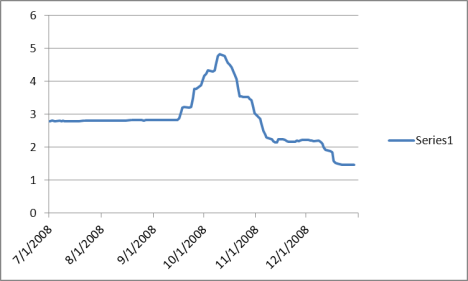

First, just as background, take a look at a graph of LIBOR rates throughout the worst of the crisis, starting in pre-crisis July and ending in December.

What was basically a flat-line through mid-September starts to spike on the day that Lehman failed, and continued to rise quite drastically every day, by about 200 basis points in the span of less than a month, until the Fed began in earnest its efforts to alleviate credit fears and get the capital markets functioning again. That 200 basis point rise in the span of a few weeks really is quite extraordinary, and is testament to the degree to which fear had taken over the market, and the extent to which credit markets had seized up. It is also testament to the fact that, whatever individual banks were submitting to the BBA as reported LIBOR contributions, LIBOR itself was clearly reflecting deep problems in the credit market. As I said, a 200 bp move in such a short time really is quite extraordinary.

Should the spike have been even sharper, but for the “false” reporting of banks such as Barclays? Perhaps. But consider the possibility that at times Barclays (and others?) probably couldn’t borrow at all in the interbank markets. Again, fear was rampant, and everyone was hoarding cash. Many banks that had cash were holding it as reserves rather than lending it out regardless of the rate. The credit markets had largely stopped functioning. So what is a contributing member of the LIBOR panel supposed to report as its borrowing rate when it hasn’t been able to borrow at all? Infinity? It is possible that the whole process of establishing a LIBOR rate could/should have broken down entirely.

Consider also the fact that members of the BBA’s LIBOR panel were placed in a distinctly disadvantageous market position relative to non-members. A non-member would have no obligation to post daily proclamations of their ability (or lack thereof) to borrow in the interbank market, and so would have less to fear from a negative feedback loop, whereby increasing credit fears lead to rising borrowing costs, which in turn would lead to even more increasing fears about one’s ability to pay it off, thus sparking even higher borrowing costs. LIBOR panel members, on the other hand, were in a position of having to announce to the world every day at 11 am GMT just how much the rest of the interbank market feared their collapse. Honesty, that is, had the potential to do even more damage to the company than was already occurring.

Finally the Fed, along with other central banks, was clearly spending much of its time trying to quell the contagion of credit fear. They didn’t want LIBOR increasing by leaps and bounds every day either, and would certainly have been in daily contact with all of the major banks. So I find it entirely plausible that either or both the Bank of England and the Fed knew of any low-balling of the submissions and either explicitly or implicitly approved it.

Again, I am not necessarily trying to absolve Barclays or anyone else of any possible wrong-doing here. Even given the points I’ve raised, I don’t know for sure what the right course of action was. But I do think it is necessary to judge whatever was done in the context of the times. We were in extraordinary circumstances and in some respects in entirely uncharted territory. In such circumstances, it is not clear to me that the normal rules necessarily apply.

(I fear that my points above are not as clear or coherent as I would like them to be. I am currently working on 3 hours of sleep in the last 2 days, and am falling asleep as I write, but I really wanted to get this up today, so I hope it at least makes some sense and you can get the gist of what I am trying to say.)

Filed under: Big Banks |

“The credit markets had largely stopped functioning. So what is a contributing member of the LIBOR panel supposed to report as its borrowing rate when it hasn’t been able to borrow at all? Infinity?”

The thing is, I think there would have been a number at which a bank would have been willing to lend to another bank. Maybe it would have been another 100 bp’s higher, maybe 200, but at some rate, another bank would have been willing to lend. The markets were frozen because it cost the bank more a higher rate than they were willing to borrow at. Maybe I’m playing semantic games, but you’ll notice the rate started falling almost as steepy when the Congress decided to “do something.” What I’m driving at is that we didn’t let the panic pass. Eventually, and sooner rather than later I think, the market would have started moving again but with, for a while anyway, a very high rate. That would have sucked, yeah, but any more so than it does now? Plus, we now have a worse problem because there is an expectation of government intervention in the future, and the thresholds in the future will be lower, and keep getting lower. Is something being too expensive a reason for massive Government intervention?

LikeLike

Thanks for the detailed posts. I will write a response once I have enough time to put something together that’s a worthy response. I’ve been busy as well and will be traveling tomorrow for business.

LikeLike

I’m not sure if this is behind the WSJ firewall or not, but there was an interesting editorial on the LIBOR issue today. It included a transcript of a conversation between a Barclays executive and Fabiola Ravazzolo, a Fed official.

Another conversation between a Barclays trader and a different Fed official:

As the WSJ goes on to say, “It would be a strange, not to say incompetent, criminal conspiracy if traders were openly discussing it with government officials.”

LikeLike

“As the WSJ goes on to say, “It would be a strange, not to say incompetent, criminal conspiracy if traders were openly discussing it with government officials.””

Unless the government is in on the conspiracy. You presume that they view their primary mission as law enforcement as opposed to maintaining the financial system.

My perspective is that during the financial crisis, the government regulatory officials effectively became unindicted co-conspirators after the fact. A prime example was the pressure placed on Bank of America to complete the Merrill Lynch deal even after their due diligence showed problems with Merrill and BoA had to effectively lie to it’s own shareholders.

LikeLike

jnc:

Unless the government is in on the conspiracy.

You’ve been reading too much Taibbi. If the police ignore the fact that everyone on the road is traveling over the speed limit, they may be negligent in their duty, but that doesn’t mean they have joined a conspiracy to break the speed limit.

You presume that they view their primary mission as law enforcement as opposed to maintaining the financial system.

Actually I don’t at all.

A prime example was the pressure placed on Bank of America to complete the Merrill Lynch deal even after their due diligence showed problems with Merrill and BoA had to effectively lie to it’s own shareholders.

We probably are in agreement with regards to the propriety of the pressure placed on BOA, but pressuring someone to do something they don’t want to do is entirely different from conspiring with that someone. It’s nearly the opposite of a conspiracy, in fact.

LikeLike

And speaking Taibbi, I thought James Taranto’s take on him from the other day was spot on:

LikeLike