Vital Statistics:

| Last | Change | Percent | |

| S&P Futures | 2090.5 | 0.3 | 0.01% |

| Eurostoxx Index | 2888.6 | 23.9 | 0.83% |

| Oil (WTI) | 48.03 | -0.3 | -0.62% |

| LIBOR | 0.646 | 0.015 | 2.38% |

| US Dollar Index (DXY) | 95.66 | -0.488 | -0.51% |

| 10 Year Govt Bond Yield | 1.44% | -0.03% | |

| Current Coupon Ginnie Mae TBA | 106.2 | ||

| Current Coupon Fannie Mae TBA | 105.6 | ||

| BankRate 30 Year Fixed Rate Mortgage | 3.53 |

Markets are flattish as we head into a 3 day weekend. Bonds and MBS are up.

Bonds will close early today and most of the Street will be on the LIE by noon.

Manufacturing picked up in June, according to the ISM Manufacturing Survey. New orders were up while prices paid fell.

Construction spending fell 0.8% in May versus an expected increase of 0.6%. April was revised downward from -1.8% to -2%. Homebuilding was flat versus April and is up 5.3% on a year-over-year basis.

Vehicle sales are coming in this morning, and they look light generally.

Overnight, the 10 year yield touched 1.38%, which is a record low on the 10 year. It looks like we are getting ready for another refi boom. Vanguard, Blackrock, and Guggenheim are all making the call that Brexit means slower growth and lower rates for the next couple of years. How pension funds and insurance companies, which need to earn 7% or more to keep up with liability growth will do that is beyond me.

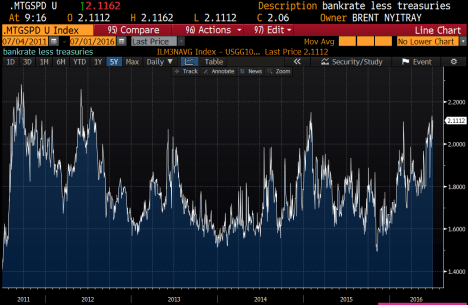

Note that the Bankrate 30 year fixed rate mortgage rate is still about 20 basis points higher than the record low set in late 2012. Mortgage backed securities have lagged the move up in Treasuries. Below is a chart of the Bankrate 30 year fixed rate mortgage rate versus the 10 year yield. The top line is mortgage rates, the lower line is the 10 year yield. If you look at the 2012 period, you can see that the 10 year yield bottomed out in July, and started rising into the end of the year. Mortgage rates kept falling throughout the year, bottoming out in December. So, mortgage rates didn’t bottom out until 5 months after Treasuries did.

If you plot the difference between the two rates (basically a proxy for MBS spreads), you can see that the current difference is approaching a high again. If this is a truly mean-reverting series, you should expect that gap to close over time, and that will either happen through higher Treasury yields or lower mortgage rates. Given the momentum in the Treasury markets at the moment, it is probably mortgage rates that will have to give. Which means we could have a good refi season into the end of the year.

The worlds’ central bankers are being forced to take the global economy into account more and more. Brexit gives Janet Yellen the excuse to hold off on hiking rates until we see inflation in the US. The ECB and the Bank of England are looking at easing. Could the next move by the Fed be some sort of stimulative measure, like bringing back QE or cutting the Fed Funds rate back down to .25%? It is definitely a non-zero probability.

The discussion draft of the bill to reform the CFPB is out. The main changes would be to bring the agency under Congressional control (it nominally reports to the Fed, but in reality it reports to no one) and to replace a single director with a bipartisan board of 5. It will also make some changed aimed at curbing the most abusive practices of the agency. While the Elizabeth Warren wing of the Democratic party will fight this tooth and nail, the affordable housing lobby is getting sick and tired of tight credit. Note that the President doesn’t think there is an issue, and even if there was, it isn’t his fault. Quote from the article:

Bloomberg Magazine: “Some of the rules put in place have meant it’s harder to get a loan. Something like 58 percent of approved mortgages are going to the wealthiest applicants, and homeownership among African Americans is down. Where’s the balance there?

Obama: “Well, the interesting thing—and we’ve looked at this very carefully—is that there’s no doubt that there’s been some pullback and increased conservatism on the part of lenders. But oftentimes, it’s not justified by the regulations”

Filed under: Economy, Federal Reserve, Morning Report |

I find it hilarious how #HeterosexualPrideDay has touched such a nerve,,, The outrage is unbelievable…

LikeLike

If enough women show up it’ll be a success, Brent. Sorta like girls 1/2 price night out at the bar.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A: I don’t understand why they would expect this stuff. It’s like it takes them totally by surprise.

B: Why can’t someone be proud of their heterosexuality? You’re only allowed to be proud of some kinds of sexuality? Huh.

C: As Einstein said, what God gives to one, God gives to all. If Black Pride is a thing, then all forms of racial pride can be a thing. If Gay Pride is a thing, then all kinds of sexual orientation based pride can be a thing.

D: The angry reaction can be angry as it wants, it’s ultimately a doomed waste of time. The only response has to be: “I can be proud of my sexuality if I want. And you can’t stop me.” – “Blah-blah-blah-oppression-blah-blah-blah-privilege!” – “Eh, I’m still proud. Straight and proud. So what?”

LikeLike

http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2016/06/29/why-heterosexualprideday-which-trending-worldwide-misses-point/86508430/

“There are, however, no countries where being heterosexual is illegal.”

Yet.

“If you genuinely feel you need a #HeterosexualPrideDay, read this:”

What if I just want to celebrate a #HeterosexualPrideDay? Not everything has to be a need.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/heterosexualprideday-trending-twitter-people-livid-124614389.html

Anyone who can make a big deal out of this, gay or straight, is affluent and privileged and spoiled beyond all measure. #NoSenseOfIrony.

LikeLike

I was serious that this works if women will show up. That Gay Pride stuff is often an excuse for many to leave work, drink, and hook up. So single men will show up for Straight Pride Parades and it will all work out to everyone’s liking if single women show up. And the proud straight single women will be popular.

Otherwise it’ll flop.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Women are already on to this.

LikeLike

With all the social justice warriors looking for an excuse to string you up by your thumbs, you would have to be nuts to try and hook up there… Nothing but a minefield.

LikeLike

Love this line from Kevin Williamson’s anti-endorsement of Trump:

http://www.nationalreview.com/article/437370/donald-trump-gop-must-say-no-him

And that is what he is: morally, intellectually, and politically unfit for office. Is Hillary Rodham Clinton actually Satan in the flesh? Of course Hillary Rodham Clinton is actually Satan in the flesh; Donald Trump is still unfit for office.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another great KW line, on Neil deGrasse Tyson’s latest demonstration of his immunity to embarrassment:

http://www.nationalreview.com/article/437324/neil-degrasse-tysons-rationality-pipe-dream

Professor Tyson, who may be the dumbest smart person on Twitter, yesterday wrote that what the world really needs is a new kind of virtual state — he wants to call it “Rationalia” — with a one-sentence constitution: “All policy shall be based on the weight of evidence.” This schoolboy nonsense came under withering and much-deserved derision.

LikeLike

As indeed it should. At the very least, it begs much more discussion. What constitutes evidence? How much is required for something to be regarded as proven? It’s one thing to repeatedly demonstrate the properties of gravity on our planet, quite another to accurately predict the future—which a great number of rational scientist purport to be able to do, even in very complex system where the record of prediction accuracy is not very great.

Then there’s a matter of desirable goals. Never mind determining what the best way to provide a living wage is, is it even desirable? Who decides that? What is the best way to execute criminals guilty of capital offenses? Should we even do it? Who decides? What’s the best way to provide an abortion, sure, but should we even do it? There is no “weight of evidence” argument that settles matters like “should we go to war” or “should abortions be legal” or “should we have capital punishment”.

This. This is exactly right. One might debate Paul Krugman’s abilities regarding complex cogitation since 1995 or so, but the point is we have great difficulty accurately predicting things that, in retrospect, seem pretty damned obvious, and where the dots are easy to connect . . . in retrospect. Believing that we have the ability to accurately predict that, say, a carbon tax with help end global warming while having no measurable impact on the economy is hugely irrational, yet I have little doubt that’s the kind of “weight of the evidence” Dyson is arguing for.

This is a universal problem with modern intellectuals (and, I’m sure, has always been to some extent), in that everything is viewed through the lens of their worship of Science and Rationality, and their view of themselves as smarter and better educated and more subtle and thoughtful than anyone who disagrees with them about anything. While it’s true that opinions do not trump data, rationalist in the Tyson mold tend to have very broad definitions of “data” and often seem to believe that the data implies things about their opinions that make them naturally superior to other opinions, or at the very least gives them a varnish of scientific truth they do not deserve or have not earned.

And I would argue further most of these folks aren’t interest in a truly rational state. Assuming that we could agree that taxes and entitlements should be shaped and reshaped until we had the optimum society, there would be immediate arguments about what was actually working and, if failures were being admitted, the causes and best solutions. People do not want to simply abandon a bad idea, and government rarely does so. People who want to tax CEOs punitively might not be interesting in letting the tax lapse, even if it turns out to be ineffective and doing whatever it was supposed to do, and vice-versa.

I think an early conclusion one might draw from the ACA, for example, is there is probably a better and cheaper way to get more American’s insured. Is the ACA going away? No.

Given the state of terrorism in our world, one might decide there is a better way to conduct the War on Terror, but we’re staying the course. Programs may be years beyond their usefulness, and we continue to fund them.

Impossible to have any kind of state, virtual or otherwise, where everything is decided on “the weight of the evidence”.

LikeLike

No one really expected anything else, did they?

LikeLike

Nope, and I haven’t expected Lynch to go after Clinton in any case, but it’s interested that it sees like Clinton basically ambushed Lynch:

LikeLike

KW:

…but it’s interested that it sees like Clinton basically ambushed Lynch

There is only one reason for him to have ambushed her. And it wasn’t to talk to her about the golf courses he was playing.

LikeLike

Either it had to do with the potential of investigating into Hillary and/or the Clinton foundation, or he really wanted to give her a back rub.

LikeLike

It was to tell her there is a million dollar job at the Clinton Foundation waiting for her if she just plays ball…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I bet he walked aboard, said “Hello Supreme Court Justice Lynch,” turned around and left.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I want to know what goes on in the basement that you can be punished for being there.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/buying-organic-groceries-in-brooklyn-can-be-a-serious-trial-1467315599

LikeLike

McWing:

I want to know what goes on in the basement that you can be punished for being there.

This story made me wonder, in light of SCOTUS’s latest ruling that it is perfectly constitutional for the government to force a pharmacist to stock certain drugs to which the pharmacist is religiously opposed, can the government impose a law forcing an organic store to stock non-organic goods? If not, why not?

LikeLike

Cannot deny legally available health care to the public if you are a licensed pharmacist. Cannot force a grocery to sell food that is not in its marketing plan.

LikeLike

Mark:

Cannot deny legally available health care to the public if you are a licensed pharmacist. Cannot force a grocery to sell food that is not in its marketing plan.

Which part of the constitution gives the government the power to dictate to pharmacists what their “marketing plan” must be, but exempts grocers from being subject to the same power?

LikeLike

Mark:

Business owner X does not want to sell product Y. Does the government have the authority to force X to sell Y?

LikeLike

Scott – the Supremes simply declined to over turn WA’s regulation of pharmacies.

Long-standing state regulations required Washington pharmacies to stock a “representative assortment of drugs in order to meet the pharmaceutical needs of … patients.” The requirements were updated in 2007, specifying that pharmacies must deliver all FDA-approved drugs to customers; they can’t refer people to get medication at a different location for any kind of religious or moral reasons.

If you want a pharmacy license in WA, follow WA law.

At a technical legal level this case differs from Hobby Lobby in that HL was brought under RFRA while this case attacked a state licensing statute and regulations which were not subject to RFRA.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Scott, one further point, this case is controlled by Scalia’s peyote decision,from 26 years ago.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/494/872

LikeLike

Mark:

Scott – the Supremes simply declined to over turn WA’s regulation of pharmacies.

I think they declined to even hear the case, which I guess is effectively the same thing.

The requirements were updated in 2007, specifying that pharmacies must deliver all FDA-approved drugs to customers; they can’t refer people to get medication at a different location for any kind of religious or moral reasons.

Correct. In other words, they can refer people to other locations for other reasos, just not for religious reasons. How that is not an obvious violation of the first amendment is quite beyond me.

If you want a pharmacy license in WA, follow WA law.

This seems to be the go-to argument for defenders of this law (I have heard it dozens of times since SCOTUS’s refusal to hear the case) but it is a complete non-sequitur. No one is arguing that pharmacists shouldn’t have to follow WA law. The argument is that WA law must be constitutional, and this one isn’t.

It is akin to having argued against Obergefell by saying that if you want to get a marriage license in Ohio you have to follow Ohio law, and thinking that settles the issue.

Scott, one further point, this case is controlled by Scalia’s peyote decision,from 26 years ago.

Personally I think there is a difference between laws that prohibit action, as in the peyote case, and laws that compel action, as in the WA case. However, that being said, if you read Scalia’s opinion he says:

But the “exercise of religion” often involves not only belief and profession but the performance of (or abstention from) physical acts: assembling with others for a worship service, participating in sacramental use of bread and wine, proselytizing, abstaining from certain foods or certain modes of transportation. It would be true, we think (though no case of ours has involved the point), that a state would be “prohibiting the free exercise [of religion]” if it sought to ban such acts or abstentions only when they are engaged in for religious reasons, or only because of the religious belief that they display.

It seems to me that a law which makes it illegal for a pharmacist to refrain from filling a prescription, or to refer a customer to another pharmacy, for religious reasons is the very epitome of the kind of law Scalia was talking about. It is difficult for me to see how there can be any reasonable debate about that.

And quite beyond the weeds of First Amendment law, it seems to me that any society in which the government seeks to compel a vendor to make a specific product available for sale despite the vendor’s objection to that product, whether for religious or any other reason, has no business calling itself a free society. Fascist is a more apt characterization.

LikeLike

Scott, there are so many legitimate reasons to refuse professional services that I cannot cover all of them.

Fraud,[this is a big one according to my daughter – people with narcotic Rxs who come in too often, men with steroid Rxs who come in too often, etc.]

Clinical [the pharmacist thinks the MD has prescribed the wrong drug or the patient has been prescribed multiple drugs some of which are contraindicated with each other],

Business [such as the additional paperwork required for controlled substances in a one person pharmacy]

Skill [such as the drug might require compounding]

Financial reasons in the small pharmacy [such as a drug’s short shelf life, the possibility that the drug might attract crime,or not wanting to stock medications that fall outside of the pharmacy’s niche, such as pediatrics, diabetes,nuclear, or fertility, or because they do not take Medicare or Medicaid or even a patient’s particular private insurance].

Another area that comes up is one of professional discretion – for example, the pharmacy has a fully therapeutic generic, but the patient only wants the brand she saw on TV – she gets referred, too.

Washington has chosen to regulate its profession according to professional standards and has excluded non-medical moral objections as a reason not to carry and dispense an FDA approved drug. That Washington has chosen to do this over the objection of the actual pharmacists in Washington caused the trial court to rule for permitting moral and religious objections. The reversal in the 9th was more in line with precedent. AFAIK, Washington is the only state with this regulation, and I expect it to change! When it does, the Circuit and the Supremes should keep hands off messing with the state regulation, then, too.

LikeLike

Mark:

Scott, there are so many legitimate reasons to refuse professional services that I cannot cover all of them.

Exactly, and that is precisely one of the problems. As Alito noted in his dissent to the decision not to hear the case:

Not only do the rules expressly contain certain secular exceptions, but the [district] court also found that in operation the Board allowed pharmacies to make referrals for many other secular reasons not set out in the rules. Id., at 954–956, 970–971. The court concluded that “the ‘design of these [Regulations] accomplishes . . . a religious gerrymander’” capturing religiously motivated referrals and little else. Id., at 984.

Alito went on to point out that because of this fact, the Oregon case that you cited earlier was not controlling.

In Employment Div., Dept. of Human Resources of Ore. v. Smith, 494 U. S. 872 (1990), this Court held that “the right of free exercise does not relieve an individual of the obligation to comply with a ‘valid and neutral law of general applicability.’” Id., at 879. But as our later decision in Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye made clear, a law that discriminates against religiously motivated conduct is not “neutral.” 508 U. S., at 533–534. In that case, the Court unanimously held that ordinances prohibiting animal sacrifice violated the First Amendment. This case bears a distinct resemblance to Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye.

There is little doubt that the law was specifically designed to target religiously motivated referrals. When the regulatory board first drafted its new rules, which allowed for referrals for reasons of conscience, the governor of the state objected to that allowance and publicly threatened board members with removal if they did not change it. When the Board reversed itself, the head of the board noted that “the moral issue IS the basis for concern.” And once the rule was issued, the board’s guidance explicitly noted that “The rule does not allow a pharmacy to refer a patient to another pharmacy to avoid filling the prescription due to moral or ethical objections.” Again, there is no doubt whatsoever that the rule targeted religious pharmacists. As I pointed out earlier, this is the very epitome of the type of law that, in the peyote decision, Scalia pointed out was obviously prohibiting the free exercise.

The reversal in the 9th was more in line with precedent.

As Alito pointed out, it is actually contrary to precedent, a real shocker coming from the 9th. /snark

When it does, the Circuit and the Supremes should keep hands off messing with the state regulation, then, too.

I am all for the Feds keeping hands off the states, but I am not for it picking and choosing when to do so based on policy preferences, which is how the progressives on the court do it. It is hard for me to understand how anyone who defends the Supremes interference with state regulation that effects abortion access, the right to which can be found nowhere except through the judicial hocus pocus of emanations and penumbras, can at the same time think the Court has no business interfering with state regulation that effects the right to free religious practice, a right that is not only explicitly written into the constitution, but was so important that it tops the list in the Bill of Rights.

FYI, this is Alitos dissent: http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/15pdf/15-862_2c8f.pdf

LikeLike

And Mark, to again pull out of the weeds of constitutional law and look at this from a broader perspective, what kind of society is it that uses the law to gratuitously force someone to choose between his job and his religion? A (classically) liberal, tolerant society would go out of its way to make accommodations so as to avoid such a choice from having to be made. But ours (or at least the one occupied by Washingtonians, the 9th, and the progressives on SCOTUS) is no longer such a tolerant society, and so it goes out of its way to do the exact opposite.

And yes, the regulation in question is entirely gratuitous, and exists only to punish an idea (opposition to abortifacients) not to fulfill some dire public need. Indeed, in its defense of the law, the state itself stipulated that “facilitated referrals do not pose a threat to timely access to lawfully prescribed medications.” So why the need to prevent them when done for religious reasons? We all know the answer, if we are honest. It is because it only happens with regard to abortifacients, and abortion is a political sacred cow. Any indication of opposition to that sacred cow, especially if it is religious, must be marginalized and demonized, and the person who holds it punished. That is the sole reason this type of regulation exists. You know it, and I know it. Both the 9th and SCOTUS knows it too, but they actually agree with it, and so have ruled as they have.

I think it is both appalling and depressing. This is far cry from the type of free and tolerant society we are supposed to have in this country.

LikeLike

From a broader perspective, the competing issues are generally individual religious choices vs. public necessity.

And in this instance we should always be able to recognize a religious exception for an individual because no public availabilty of a medication is threatened by even this entire pharmacy’s refusal to carry a medication.

So had I been on the Court I would have voted to take the case and reverse the appellate decision, but on very narrow religious exception grounds. I would have written that the State regulation was overbroad in its application because it did not allow for a religious exception where other sources of the medication were timely and reasonably available. I pretty much agree with the trial court.

The 9th C. used the example of the rural areas where other sources of medication were not timely and reasonably available to uphold the regulation. In other words, the 9th C. went outside the record. And that is my problem with the case.

I am less offended by the result than you are because I think a strong policy favoring state control of licensing for the learned professions is better than a national policy. And I think the policy decision to not hear this case was in part because WA is the only state that has this sweep of regulation and the Court is shorthanded. But I do think the 9thC. was wrong, on the facts presented.

LikeLike

Mark:

I am less offended by the result than you are because I think a strong policy favoring state control of licensing for the learned professions is better than a national policy.

Actually, as a matter of principle I am probably even more in favor of state control than you are. I would be far less concerned with the specific result in this case if SCOTUS was consistent in applying the principle. But of course it isn’t. As we have very recently just seen, when it comes, for instance, to licensing abortion clinics, the lock-step liberals (plus one) on SCOTUS are far more interested in preventing virtually any meaningful state control than in maintaining a strong policy favoring state control. And unless I am mistaken, you support the court’s jurisprudence with regard to abortion clinics.

LikeLike

You do not rate the want or need of these medications or of abortions very highly. I rate them more highly than you do.

We are at that divide.

LikeLike

Mark:

You do not rate the want or need of these medications or of abortions very highly. I rate them more highly than you do. We are at that divide.

Or alternatively, since what is pitted against each other here is an individual want or need for these medications versus the individual right to religious freedom, I suppose we could equally say that you don’t rate the right of religious freedom very highly. Obviously, at least, not as highly as you rate the individual want/need for these medications. In this regard, I would note that religious freedom is actually an explicitly protected right, written directly into the constitution, while access to medication at all, much less particular kinds of it, is not. And so, constitutionally speaking, I think my relative valuation is much easier to defend.

But regardless, I don’t think that really is our divide. It is possible for people to place different relative values on different things, as we apparently do with regard to abortion and religious freedom, and even to disagree over desired public policy with regard to those things, without disagreeing over the proper, constitutional source of whatever the policy might end up being. So I think our real divide is less in our relative valuation of abortion and religious freedom, and more in our willingness to apply constitutional principle without regard to the policy outcome and whether we personally find those outcomes preferable.

As I said, I would actually quite prefer (and think the constitution plainly requires) what you called a strong policy favoring state control, rather than a national policy, when it comes to regulating access to either abortion or abortifacients. And I support that principle even if it would result in some policies I like, like Texas’s more restrictive access to abortion, and others that I don’t like, like Washington state trampling on the religious freedom of pharmacists. If Washington can decide for itself that access to certain drugs is so important that it needs to restrict the constitutional right to religious freedom of pharmacists in order to achieve that, then Texas can decide for itself that safety is so important that it needs to restrict the “right” of access to an abortion in order to achieve that.

If however, as has been the case with abortion, the operable principle is that SCOTUS is going to make meaningful state regulation virtually impossible with regard to things like abortion that have been deemed (rightly or wrongly) a constitutional right, then I think that principle ought to be applied without regard to whether the particular policy outcome is personally preferable or not.

You however, seem happy to ignore the principle depending upon how you personally “rate” the thing being regulated. Hence your seemingly contradictory position on regulating pharmacies versus regulating abortion clinics. And I think that is our real divide. I rate the objective application of legal principle more highly than I do specific policy outcomes, while you seem to rate the achievement of preferrd policy outcomes more highly than you do the objective application of legal principles.

LikeLike

It seems to me that you conflate the individual’s religious liberty with a corporation’s ability to dictate religious decisions to others. I completely favor the religious exception for individuals where it can be accommodated. For example, I don’t think snake worshippers bringing rattlers to school should be accommodated. And I do think public accommodations housing more than X tenants or guests should not be able to deny Muslims, and that employers of more than x employees should not be able to determine their employment decisions on the basis of race, creed, or national origin. I believe they actually affect commerce, unless they are very small. I think this is within the spirit and letter of the commerce clause, in that it promotes the open market and no discrimination against a class of presumably American customers, and the BoR, in that no one is forcing either an establishment upon, or denying a free exercise, to the individual.

Your apparent reading is either that making someone sell birth control pills establishes a religion or prohibits the free exercise thereof.

Again, I have no problem honoring the conscience of an individual. As I said, in this case, I would have ruled with the Appellants, for exactly the reason it appears that the trial court did. But had the facts been that the customer was forced to drive 60 mi each way to get medicine I would have ruled consistently and said the religious exception cannot weigh Appellant’s “conscience” so heavily as to dictate someone else’s behavior.

And it is that reasoning, coupled with the evidence that abortions are safer than colonoscopies, that leads to the obvious conclusion that the only reason to treat abortions to an improbably high standard of medical care was to force someone’s religious belief in order to deny someone else medical care.

LikeLike

What if the majority of voters think it’s perfectly ok for Snake Worshippers to bring rattlers to schools? Is it your position the Federal Government should prevent that?

LikeLike

Local police and animal rescue should handle it.

When the snake handlers sue the cops they should lose.

If the local cops never step in, when the relatives of the snake bitten kid sue they should win.

LikeLike

To be clear though, there should be no Federal role?

LikeLike

Well, if the snake handlers claim the first amendment in their civil rights suit against the cops, the federal courts would probably be involved.

I would not want a federal legislative role in establishing criminal law in the area. I don’t even like much of federal criminal law now.

Perhaps my imagination fails me, but no federal role outside what happens in a federal courtroom seems right to me.

LikeLike

Mark:

My previous post was focused on the apparent lack of principled consistency between thinking that a state ought to be able to restrict one right (the right to the free exercise of religion) in the pursuit of some presumed state interest (convenience of access to certain drugs), but it ought not be able to restrict another “right” (the “right” to get an abortion) in the pursuit of some presumed state interest (the safety of abortions, or the protection of unborn humans). From what I can tell, you have not addressed that inconsistency at all in this post.

That being said, I will address the seemingly new topics you introduced here.

It seems to me that you conflate the individual’s religious liberty with a corporation’s ability to dictate religious decisions to others.

I am not at all sure why it would seem that way, since until this very post, the idea of a corporation has not been mentioned by either you or me.

I completely favor the religious exception for individuals where it can be accommodated.

It “can” be accommodated in literally every instance. The only thing that could ever stop the government from making an accommodation is its own will.

For example, I don’t think snake worshippers bringing rattlers to school should be accommodated.

I’m not at all sure how this relates to the situation at hand. No one is suggesting that the state ought not be able to make and enforce rules for schools that it owns and operates. The question is whether the government ought to be able coerce a private business owner to engage in business to which the owner has religious objections.

And I do think public accommodations housing more than X tenants or guests should not be able to deny Muslims, and that employers of more than x employees should not be able to determine their employment decisions on the basis of race, creed, or national origin.

I understand that these represent your preferred policies, but of course the question is not (or at least should not be) whether you like the policies, but rather whether these preferred policies are either required or allowed by the constitution. I have read the constitution and at no point that I have seen does the constitution mention the concept of “public accommodations” much less does it guarantee anyone unfettered access to them, or exempt people operating them from the general right to religious freedom. For example, the first amendment says “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, nor the free exercise thereof.” It does not say “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, nor the free exercise therof, except with regard to public accommodations.” Perhaps you can point out to me the part of the constitution that leads you to think that the Establishment clause does not apply to people operating a public accommodation, or that access to “public accommodations” is guaranteed.

Also, while it is not clear to me what relevance the commerce clause has to our discussion (we have been talking about state laws), I would also be interested in what part of the constitution indicates to you how many employees or how many customers a “public accommodation” must have before it effects interstate commerce.

I think this is within the spirit and letter of the commerce clause, in that it promotes the open market and no discrimination against a class of presumably American customers, and the BoR, in that no one is forcing either an establishment upon, or denying a free exercise, to the individual.

Again not that it has anything to do with what we have been discussing, but neither the spirit nor the letter of the commerce clause says anything about “promoting no discrimination against a class of customers.” But that aside, if the government forcing a person to engage in activity that is contrary to his religion is not a denial of the free exercise of religion, then the phrase is devoid of meaning altogether.

Your apparent reading is either that making someone sell birth control pills establishes a religion or prohibits the free exercise thereof.

If it is against the person’s religion to sell birth control pills then yes, I think it is obviously the very epitome of prohibiting the free exercise of religion to force him to do so.

But had the facts been that the customer was forced to drive 60 mi each way to get medicine I would have ruled consistently and said the religious exception cannot weigh Appellant’s “conscience” so heavily as to dictate someone else’s behavior.

I don’t understand your characterization. How is failing to sell something “dictating someone else’s behavior”? And what exactly do you think this is “consistent” with?

Beyond that, it seems to me that your position boils down to nothing more than that the “right” to convenience in obtaining a particular drug carries greater weight than does the right to exercise a religious objection to selling the drug. When obtaining the drug gets to a certain arbitrary (why 60 miles and not 100?) point of inconvenience, suddenly the right to religious freedom is tumped. As a matter of personal preference, I suppose that position could makes sense to you. But as a constitutional matter it seems to me totally indefensible. The right to free religious exercise is explicitly written into the constitution, while a “right” to convenience when buying goods and services is totally absent from it. How can a “right” which is literally never mentioned in the constitution take legal precedence over a right that is explicitly guaranteed by it?

And it is that reasoning, coupled with the evidence that abortions are safer than colonoscopies, that leads to the obvious conclusion that the only reason to treat abortions to an improbably high standard of medical care was to force someone’s religious belief in order to deny someone else medical care.

I’m not entirely sure what you are saying here, but it sounds like you are suggesting that the only possible objections to abortion that can exist are religious objections, and therefore any restrictions placed on abortions are necessarily “forcing someone’s religious belief” on others. If that is what you are saying, I myself am proof that you are wrong. I would place much greater restrictions on abortions than are currently allowed by SCOTUS, and my reasons have nothing whatsoever to do with religion.

LikeLike

Mark:

As you can see, I wrote a long response last night, probably much too long. So allow me to focus more narrowly on what seems to me the primary issue.

You said:

Your apparent reading is either that making someone sell birth control pills establishes a religion or prohibits the free exercise thereof.

As I said above, if selling birth control pills is against a person’s religion, then I do indeed think that forcing that person to sell those pills represents a prohibition on the free exercise of religion. Your implication seems to be that you don’t think it represents such a prohibition. And yet you’ve also said that you would rule that an allowance for a religious objection needs to exist, as long as that allowance doesn’t create more than a certain degree of inconvenience to someone who wants the drugs. This suggests to me that in fact you also recognize the law as a prohibition on the free exercise, because otherwise there would be no reason to require the allowance regardless of the level of inconvenience caused.

So my take on your position is that you seem to think two rights are in conflict, the right to convenient access to the drugs and the right to free exercise of religion, and that the former outweighs the latter. Is that a fair assessment?

If that is a reasonable assessment of your position, my primary objection to it is that I can’t find anything in the constitution that guarantees any such right to convenient access to drugs, and so I don’t see how it can be seen to trump the right to free religious practice, which actually is explicitly guaranteed.

LikeLike

Scott, you are coming at this from a different direction than I. I do not believe that it is a violation of the free exercise clause for a facially religiously neutral law of general application to inhibit or even in the public sense prohibit conduct. I do believe that it is a violation of the establishment clause for a state to enforce a law of general application that imposes a religious restriction on the conduct of persons who are not co-religionists. Such a law would be one in which a school district voted to allow poisonous snake handling in the schools.

As for abortion, it is currently unlawful for a state to restrict access to the point of denying access to a great many of its citizens. This case arose in the context of a corporate owner’s religious and moral beliefs, but even if an agnostic like you were the owner the restriction would be suspect, given a state law consistent with current constitutional law as it stands. However, given that this store’s refusal did not actually deny access it was overbroad.

Should a state’s ability to deny abortions be reconsidered and held constitutional? Perhaps. Abortion is sui generis as a hot button issue – what most think of as a medical issue, first, a large minority think of as a moral or religious issue, first.

If it IS a medical issue, first, then denial by the state can be seen as the establishment of religion – e.g., Roman Catholicism – quite readily. If it is a moral issue with criminal implications, first, then of course states can restrict them in many instances.

—

On the other note, I think the Commerce Clause gives Congress broad power. I do not think that it is unlimited power, in theory, but it is damned broad. If Congress finds that a business of a certain size must affect commerce among the states, then a court must rule to except the business that complains, based on very specific evidence. That the Supremes decided a farmer could not eat his own produce during price controls is an awful case of too much deference. But that doesn’t change the theory. Thus my suggestion of “x” size requirements.

The post Civil War amendments would certainly lose their meaning if black persons could be kept out of the normal commercial streams because they are – black. That there is a history of ignoring these rather obvious [to me] constitutional policies and that they have only been enforced for fifty years says that inertia is very strong in this area.

— Back to the other—

An individual doctor or pharmacist is permitted to say that her conscience forbids her aid in, or performance of, an abortion. That is the essence of reasonable accommodation to free exercise, without the state establishing that person’s religion.

LikeLike

Mark:

I do not believe that it is a violation of the free exercise clause for a facially religiously neutral law of general application to inhibit or even in the public sense prohibit conduct.

The law in question does neither. It compels conduct, it does not inhibit or prohibit it. So the question is whether a facially neutral law of general application that compels conduct contrary to a persons’ religious beliefs is a violation of the free exercise clause. To me it seems plain that it is, and your expressed belief that an accommodation is required under certain conditions (ie convenient access is not overly inhibited) implies that you agree with that. If you do not, then your belief that an accommodation is required even under limited circumstances doesn’t make sense to me.

As an aside, the fact that a law is “facially neutral” does not mean that the law is not actually targeting specific religious practices or beliefs. In fact, given that religious practices and beliefs are often defined by the fact that they are distinct to particular religions and not widely practiced, it is extremely easy to devise “facially neutral” requirements that in fact impact only the targeted religion. And such targeting strikes me also as a plain violation of the first amendment.

I do believe that it is a violation of the establishment clause for a state to enforce a law of general application that imposes a religious restriction on the conduct of persons who are not co-religionists.

Is it any less of a violation for a state to enforce a law of general application that imposes an anti-religious restriction on the conduct of persons who are not co-religionists (or co-anti-religionists, as the case may be)? While I certainly agree that the 1st amendment prevents the government from imposing, say, Jewish doctrine on those who are not Jewish, I think it also prevents the government from imposing non-Jewish doctrine on those who are Jewish.

As for abortion, it is currently unlawful for a state to restrict access to the point of denying access to a great many of its citizens. This case arose in the context of a corporate owner’s religious and moral beliefs, but even if an agnostic like you were the owner the restriction would be suspect, given a state law consistent with current constitutional law as it stands.

I think you are confusing the two issues. The constitutional status of access to abortion has no relevance to the Washington case. Abortion jurisprudence at SCOTUS (such as it is) says basically that state law cannot restrict access to abortion. It does not say that pharmacists must inventory certain drugs, nor does it pontificate on when and for what reason a pharmacist can and cannot refer customers to another pharmacist.

Abortion is sui generis as a hot button issue – what most think of as a medical issue, first, a large minority think of as a moral or religious issue, first.

I don’t understand the distinction you are drawing. Of course abortion is a “medical issue” in that it involves the practice of medicine, but it is also one that has a moral aspect to it, in that it is an action that involves more than one person. One needn’t consider one aspect to the exclusion of the other. Indeed, it is difficult for me to even imagine how one might do that.

If [abortion] IS a medical issue, first, then denial by the state can be seen as the establishment of religion – e.g., Roman Catholicism – quite readily.

Again, you seem to think that the only possible justification for opposing abortion is Roman Catholic doctrine. That assumption is plainly incorrect. Moral opposition to abortion is not even remotely limited to Roman Catholics.

On the other note, I think the Commerce Clause gives Congress broad power.

It would be fun to discuss the Commerce Clause, and I totally disagree with you on this, but I don’t think it is relevant to the issue at hand.

The post Civil War amendments would certainly lose their meaning if black persons could be kept out of the normal commercial streams because they are – black.

I think that is absolutely untrue.

The 13th amendment prohibits slavery. The 14th amendment (part 1) defines what citizenship is and then restricts the actions of state governments with regard to those citizens. Neither of those has anything to say about, nor are they impacted by, a situation in which a business owner wants to discriminate against a potential customer on the basis of race. Their meaning remains perfectly clear and useful even if a particular vendor is free to refuse service to someone on the basis of race (or any other kind of) discrimination.

I understand that in the minds of many the 14th amendment has morphed into a kind of legal magic elixir that somehow justifies any and all restrictions even on non-governmental discrimination against politically favored classes of people. But I can’t find anything in it that actually says or implies anything about what kind of commercial relationships private actors can or cannot or must engage in. It talks exclusively about how the government must treat citizens. It says nothing about how citizens must treat each other.

An individual doctor or pharmacist is permitted to say that her conscience forbids her aid in, or performance of, an abortion. That is the essence of reasonable accommodation to free exercise…

Permitted to simply say that, or permitted to actually act on it by refusing to provide such aid? If the latter, then it seems that, like me, you do indeed recognize that to force someone to engage in activity that is prohibited by their religion is a violation of their guaranteed right free exercise. So if we can agree on that, we can move on to discussing why you think a statutory right to convenient access to certain drugs can possibly trump a constitutional right to freedom of religious exercise.

LikeLike

BTW, Mark, on this:

From a broader perspective, the competing issues are generally individual religious choices vs. public necessity.

First, with regard to this specific case, access to abortifacients is not a “public necessity”. It is, at most, an individual necessity, and in reality is more akin to an individual desire.

Beyond that, what other examples of a “public necessity” can you think of that have resulted in laws compelling action (as opposed to prohibiting action) on the part of someone with a religious objection to that action? The most obvious one to me would be military draft laws, but even those have come to include conscientious objector exemption. The only other one that comes to mind is, possibly, inoculations against a contagious disease, which is a fairly unique circumstance.

I don’t think we should downplay quite how radical and out of the ordinary it is to have government compelling people to directly undertake activity to which they have moral/ religious objections.

LikeLike

Worth reading:

View at Medium.com

LikeLike

Happy to vote Libertarian this time:

“Is This Gary Johnson/Bill Weld Spot the Greatest Presidential Ad Ever?

LBJ’s Daisy, Nixon’s “Crime,” Dukakis’ “Snoopy” tank ride, you’ve got competition.

Nick Gillespie|Jun. 30, 2016 9:23 am”

http://reason.com/blog/2016/06/30/is-this-gary-johnsonbill-weld-spot-the-g

video/1

LikeLike

That was great.

LikeLike

I like it. I like them. Agree with them or not, and whether or not Johnson spends most of his time stoned, they come off way better than Trump or Hillary, IMHO.

LikeLike

KW, is there a better way of spreading that then by email with links?

What a breath of fresh air.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I posted on Facebook. Not much else for me to do about it!

LikeLike

My personal goal is to double the libertarian vote at my polling place. From 21 in 08.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What was it in 2012?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Johnson received 19 votes in my precinct in 2012

LikeLiked by 1 person

I want to know where they’re going to “spend those dollars at home”.

LikeLike

Good question. Infrastructure? Paying off on debt. I’m guessing.

LikeLike

https://johnsonweld.com/issues/

LikeLike

Happy Independence Day to all of you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person