Vital Statistics:

| Last | Change | |

| S&P futures | 2463 | -4.4 |

| Oil (WTI) | 23.84 | -0.69 |

| 10 year government bond yield | 0.81% | |

| 30 year fixed rate mortgage | 3.44% |

Stocks are flattish as volatility begins to recede. Bonds and MBS are down. The Fed should be buying another $50 billion of MBS today.

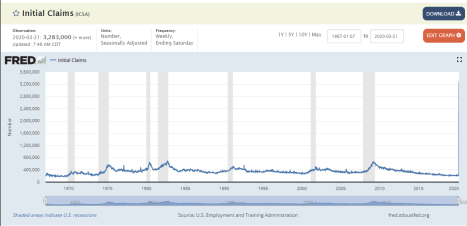

Initial Jobless Claims jumped eleven-fold to 3.3 million last week. In a period where it seems like everything is considered “unprecedented,” this one is too.

The third revision to fourth quarter GDP was unchanged at 2.1%. Estimates for second quarter GDP at this point are all across the board, but down double digits is certainly a possibility.

The Senate passed the stimulus bill yesterday and the House is trying to pass it without being in session. AOC is supposedly granstanding on this and wants to bring everyone back.

Good explainer on what is happening in the mortgage REIT sector. Essentially, the non-agency REITs are the big buyers of non-QM paper, and they are getting margin calls. While much of this non-QM paper is probably money good, it doesn’t matter. Also, servicers are getting slammed as well. Suffice it to say the buyers of non-QM paper, assuming they make it through this whole thing, are probably going to have a much lower appetite going forward. The non-QM market is probably going to be on hold for a long time. Annaly and AGNC are doing the best in this market, although even they are not immune.

The House’s stimulus bill included language for a Fed servicing advance line to be extended to servicers who go along with the program and let people defer mortgage payments during the crisis. The big Ginnie servicers are going to need the help.

The government is considering taking equity stakes in the airlines as part of a bailout package.

Redfin is seeing a 27% decrease in traffic due to the Coronavirus, but it is still flat on a YOY basis. Remote tours are becoming more popular. Note that all of the ibuyers (Zillow, OpenDoor and Redfin) have all suspended buying.

Filed under: Economy, Morning Report |

What does Zillow buy aside from information?

LikeLike

They buy houses. (or at least they did until the crisis). Zillow Offers.

Zillow will bid on your home on a non-contingent basis in several markets.

I did a piece on it not too long ago:

https://www.fool.com/investing/2020/03/02/the-challenges-zillow-faces-in-its-homebuying-busi.aspx

LikeLiked by 1 person

They put out a good offer price for my home last year but then they take something like a 20% commission to bring their cash outlay to well below market value. If you have a lot of equity and want a fast sale, it’s a route.

LikeLike

I thought their normal fee was about 7.5%, so that is a lot different.

LikeLike

It was huge.

LikeLike

From a CPA newsletter circulated to my favorite CPA; the author quoted some from Sen. Grassley’s newsletter. –

Section 2301 Employee retention credit for employers subject to closure due to COVID-19

The CARES act provides a tax credit based on wages. That credit equals 50 percent “of wages paid by employers to employees during the COVID-19 crisis” and it applies to “the first $10,000 of compensation, including health benefits, paid to an eligible employee.”

Example: You have ten employees who each make $2000 a month. To keep the example simple, suppose that healthcare benefits run $500 a month per employee. In total, then, each employee costs $2500 a month and over the next four months, the employer would spend $10,000 on each employee.

The Section 2301 “employee retention credit” gives you, the employer, a $5,000 tax credit. That’s per employee. With ten employees, then, you enjoy $50,000 in tax credits.

Some details to know…

The tax credit is what’s called a “refundable tax credit.” That means you get the credit regardless of whether you’ve paid taxes.

Example: Your business generates no taxable income due to the COVID-19 crisis. As a result, you pay no income taxes. You still get a $50,000 “tax refund.”

Another thing to know? Not every employer qualifies but the rules are pretty loose. An employer may use the credit if “operations were fully or partially suspended, due to a COVID-19-related shutdown order” or if quarterly revenues shrink by more than 50 percent as compared to the previous year.

An obvious comment maybe: You’ll need a real accounting system to easily determine whether you qualify based on a decline in quarterly revenues.

One other thing to note: The formula works differently for employers with more than 100 full-time employees than it does for smaller employers. For “big” small businesses, the formula looks only at ”wages paid to employees when they are not providing services due to the COVID-19-related circumstances.” Again, this means you’ll need a good accounting system operating to determine this.

For “small” small businesses, so those with 100 or employees or less, the formula just says “all employee wages qualify for the credit, whether the employer is open for business or subject to a shut-down order.”

Section 2302 Delay of payment of employer payroll taxes

The CARES act provides another small-business-friendly tax break related to employee costs: a deferral, or delay, in when you remit payroll taxes.

As you probably know, employers pay a 6.2% Social Security on most wages. Usually during or by the end of each quarter. Note that this employer Social Security tax isn’t the only payroll-related tax an employer pays. But it’s a significant one.

Example: An employer pays $10,000 in wages for the current payroll period. As part of the payroll, the employer calculates and withholds federal and state income taxes that tally $1000, Medicare taxes paid by both the employer and employee that add up to $300 or so, Social Security taxes paid by both the employer and employee that add up to roughly $1200, and a few other state-specific taxes. The Section 2302 deferral applies to the 6.2% employer Social Security, or $620.

How long does an employer get to delay? Two years. Half in 2021 and half in 2022.

By the way? Talk with your accountant about whether or not this deferral really makes sense. I’m not sure you want to get behind on your payroll taxes…

Section 2303 Modifications for net operating losses

Perhaps the most interesting small business friendly tax break? The loosened rules for using net operating losses.

The CARES act allows a business owner to carryback a net operating loss from 2018, 2019 or 2020 to the previous five years.

Example: The COVID-19 crisis creates a net operating in your business for 2020. Say, for sake of illustration, that you lose $100,000. The new rules allow you to take this $100,000 “net operating loss” and treat it as a deduction on an amended 2016 tax return. If that year, so in 2016, you made $300,000, you’ll essentially “redo” your 2016 tax return only this time with an extra $100,000 tax deduction, which means your taxable income drops from $300,000 to $200,000. That tax deduction may create a $25,000-ish refund.

A caution: You will probably need your accountant’s help to handle the net operating loss carryback. His or her other clients will very possibly need the same help. Accordingly, if you think this tax break applies, you’ll want to get into the queue quickly.

Let me also say that historically the IRS takes a while to pay net operating loss refund claims. And the larger the claim, the longer the processing times. Probably we’re talking weeks at the minimum. I would not be surprised if these refunds take months.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mark.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quicken could be in trouble if there is massive mortgage forbearance and the government doesn’t provide a lending facility for it

https://www.freep.com/story/money/business/2020/03/24/coronavirus-covid-19-quicken-loans-temporary-funding/2907948001/?fbclid=IwAR1nxQWSbU-7Kxl5wl5TIoEKDPhy1bH6srV_LixOymX59Qa3eV3M5ZimrSU

LikeLike

I think this is out from behind the firewall. Worth a read.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/is-the-coronavirus-as-deadly-as-they-say-11585088464

LikeLike

It’s behind the paywall.

LikeLike

Damn the WSJ. I was told they eliminated the paywall for 30 days over covid.

If it’s true that the novel coronavirus would kill millions without shelter-in-place orders and quarantines, then the extraordinary measures being carried out in cities and states around the country are surely justified. But there’s little evidence to confirm that premise—and projections of the death toll could plausibly be orders of magnitude too high.

Fear of Covid-19 is based on its high estimated case fatality rate—2% to 4% of people with confirmed Covid-19 have died, according to the World Health Organization and others. So if 100 million Americans ultimately get the disease, two million to four million could die. We believe that estimate is deeply flawed. The true fatality rate is the portion of those infected who die, not the deaths from identified positive cases.

The latter rate is misleading because of selection bias in testing. The degree of bias is uncertain because available data are limited. But it could make the difference between an epidemic that kills 20,000 and one that kills two million. If the number of actual infections is much larger than the number of cases—orders of magnitude larger—then the true fatality rate is much lower as well. That’s not only plausible but likely based on what we know so far.

Population samples from China, Italy, Iceland and the U.S. provide relevant evidence. On or around Jan. 31, countries sent planes to evacuate citizens from Wuhan, China. When those planes landed, the passengers were tested for Covid-19 and quarantined. After 14 days, the percentage who tested positive was 0.9%. If this was the prevalence in the greater Wuhan area on Jan. 31, then, with a population of about 20 million, greater Wuhan had 178,000 infections, about 30-fold more than the number of reported cases. The fatality rate, then, would be at least 10-fold lower than estimates based on reported cases.

Next, the northeastern Italian town of Vò, near the provincial capital of Padua. On March 6, all 3,300 people of Vò were tested, and 90 were positive, a prevalence of 2.7%. Applying that prevalence to the whole province (population 955,000), which had 198 reported cases, suggests there were actually 26,000 infections at that time. That’s more than 130-fold the number of actual reported cases. Since Italy’s case fatality rate of 8% is estimated using the confirmed cases, the real fatality rate could in fact be closer to 0.06%.

In Iceland, deCode Genetics is working with the government to perform widespread testing. In a sample of nearly 2,000 entirely asymptomatic people, researchers estimated disease prevalence of just over 1%. Iceland’s first case was reported on Feb. 28, weeks behind the U.S. It’s plausible that the proportion of the U.S. population that has been infected is double, triple or even 10 times as high as the estimates from Iceland. That also implies a dramatically lower fatality rate.

The best (albeit very weak) evidence in the U.S. comes from the National Basketball Association. Between March 11 and 19, a substantial number of NBA players and teams received testing. By March 19, 10 out of 450 rostered players were positive. Since not everyone was tested, that represents a lower bound on the prevalence of 2.2%. The NBA isn’t a representative population, and contact among players might have facilitated transmission. But if we extend that lower-bound assumption to cities with NBA teams (population 45 million), we get at least 990,000 infections in the U.S. The number of cases reported on March 19 in the U.S. was 13,677, more than 72-fold lower. These numbers imply a fatality rate from Covid-19 orders of magnitude smaller than it appears.

How can we reconcile these estimates with the epidemiological models? First, the test used to identify cases doesn’t catch people who were infected and recovered. Second, testing rates were woefully low for a long time and typically reserved for the severely ill. Together, these facts imply that the confirmed cases are likely orders of magnitude less than the true number of infections. Epidemiological modelers haven’t adequately adapted their estimates to account for these factors.

The epidemic started in China sometime in November or December. The first confirmed U.S. cases included a person who traveled from Wuhan on Jan. 15, and it is likely that the virus entered before that: Tens of thousands of people traveled from Wuhan to the U.S. in December. Existing evidence suggests that the virus is highly transmissible and that the number of infections doubles roughly every three days. An epidemic seed on Jan. 1 implies that by March 9 about six million people in the U.S. would have been infected. As of March 23, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 499 Covid-19 deaths in the U.S. If our surmise of six million cases is accurate, that’s a mortality rate of 0.01%, assuming a two week lag between infection and death. This is one-tenth of the flu mortality rate of 0.1%. Such a low death rate would be cause for optimism.

This does not make Covid-19 a nonissue. The daily reports from Italy and across the U.S. show real struggles and overwhelmed health systems. But a 20,000- or 40,000-death epidemic is a far less severe problem than one that kills two million. Given the enormous consequences of decisions around Covid-19 response, getting clear data to guide decisions now is critical. We don’t know the true infection rate in the U.S. Antibody testing of representative samples to measure disease prevalence (including the recovered) is crucial. Nearly every day a new lab gets approval for antibody testing, so population testing using this technology is now feasible.

If we’re right about the limited scale of the epidemic, then measures focused on older populations and hospitals are sensible. Elective procedures will need to be rescheduled. Hospital resources will need to be reallocated to care for critically ill patients. Triage will need to improve. And policy makers will need to focus on reducing risks for older adults and people with underlying medical conditions.

A universal quarantine may not be worth the costs it imposes on the economy, community and individual mental and physical health. We should undertake immediate steps to evaluate the empirical basis of the current lockdowns.

Dr. Bendavid and Dr. Bhattacharya are professors of medicine at Stanford. Neeraj Sood contributed to this article.

LikeLike

8% is estimated using the confirmed cases, the real fatality rate could in fact be closer to 0.06%.

Which is a bad flu year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The true fatality rate is the portion of those infected who die, not the deaths from identified positive cases.

Are they saying that the test has a massive false positive rate? I haven’t seen that anywhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brent:

Are they saying that the test has a massive false positive rate?

No, I think they are saying that a lot of people who are infected haven’t been, and may never be, tested.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think this is correct–that a large number of infected individuals have not been identified and will not be. I think the contagion level has been inflated, too–because the virus has had lots of time to spread, like a flu, and then testing ramped up quite rapidly, giving us the impression of this rampaging contagion because we’re equating a increase in testing frequency with transmissibility–when I think it probably transferred at a normal, if highly contagious rate, and then the sudden increase in testing (and the testing’s focus on those suspected or known to have been exposed) gave the impression that it was off-the-charts contagious. When in fact it may be no more contagious than the common cold and no more fatal than an average or slightly-above-average flu.

Part of the problems are the numbers being bandied about. The first study that everybody was going on to help make everyone terrified turns out to have been a wee bit overblown:

https://www.dailywire.com/news/epidemiologist-behind-highly-cited-coronavirus-model-admits-he-was-wrong-drastically-revises-model?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=benshapiro

LikeLike

Under the Senate bill, the borrower must be affected by the coronavirus, however the only proof required is the borrower’s attestation. And, the servicer is not permitted to ask for anything more.

recipe for borrower fraud galore. And of course the next D admin is going to sock all the banks under the false claims act when it needs money.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting chart here:

https://www.vox.com/2020/3/26/21193848/coronavirus-us-cases-deaths-tests-by-state

LikeLike

The number of cases have a direct correlation to the number of tests. Suggesting that the number of cases is being determined by the number of tests.

LikeLike

Senate bill, page 565 the language on mortgages starts

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6819239-FINAL-FINAL-CARES-ACT.html

borrower just has to say “I’m affected” and the servicer must report the loan as current.

why is anyone going to pay their mortgage for the next year?

and if you have an income property and your renter stops paying, what do you do? I think this is only for primaries.

They have not thought this through at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unless it includes a rent holiday, the left will go apeshit over this

LikeLike

As well they should. The problem with doing this stuff is that it will be discriminatory against someone, and there will be a case where a dude with a fat income and lots of cash is getting a break and some poor sod just trying to make the rent gets squat. And boy will we being hearing those stories on NPR.

LikeLike

why is anyone going to pay their mortgage for the next year?

I’m going to, because I feel like I’m demonstrably not-affected. If a credit card issuer however said they wouldn’t charge interest for a year if I said I was affected by corona virus, I’d probably chance it anyway. That would just be money I would otherwise have to pay going away.

If the deal involved every payment I made on my mortgage going straight to principal while no interest was collected for the rest of the year–heck, I’d give it a try. But if it doesn’t produce any “new” money for me, there’s no reason to not go ahead and pay my mortgage.

LikeLike